Artists and Sustainability Spotlight: Elliott Flanagan

Posted on 19 September 2025

This month we’ve invited Elliott Flanagan to contribute to our ongoing series Artists and Sustainability Spotlight, where we ask artists to share short responses about their work and how it might relate to climate change.

Elliott Flanagan is a multimedia artist and writer. He works at the intersection of several subjects: identity, youth, memory, class, and unpicks contemporary masculinity. He is interested in their relationship to popular culture, exploring ideas of our inner lives and transfiguration via psychogeographic dreams and disorienting post-industrial backdrops. His practice brings together text, film, sound, installation, performance, and spoken word to mix personal, social and historical stories. He is passionate about art and culture for all.

Commissioned by Super Slow Way, Elliott is currently showing his solo exhibition, You can never really return home, at the Salon in his hometown, Burnley, UK. His book Recreation was published by Pendle Press in 2023. He was commissioned by Venture Arts the same year to work with learning disabled artists collaborating with artist Barry Finan at The Hand that Makes the Sound at Tate Liverpool, and at Baltic Gateshead with Project Art Works for Explorers Project event 2023. His poetic work Blancmange, was a book and moving image work for A Modest Show, part of British Art Show 2022. In 2024, two of Flanagan’s poems were published in Masculinity: an anthology of modern voices by Broken Sleep Books. He has been a resident DJ at Slack’s Radio, has written for The Fourdrinier, and has exhibited nationally and internationally including HOME (2021), g39 Cardiff, Venice Biennale and Begehungen, Chemnitz (2019). He is based in the North West, UK.

His books You can never really return home, Recreation, and Blancmange are now available online in the Castlefield Gallery shop.

In what ways do you feel your work might relate to issues of climate change and sustainability, in the content of the work, its narrative, conceptually or theoretically. How might it speak to or challenge public discourse?

In much of my practice, we encounter the rural and while my practice isn’t outright climate activism, I am politically and socially engaged. As a result, I keep up with the current climate discourse, have it in mind and through reflections in my work on the countryside and landscape, I am calling for its protection and paying mind to our responsibilities to keep it flourishing, to protect and ultimately, ensure its survival. It is a recurring theme.

In my most recent project, You can never really return home (2025), I was commissioned by Super Slow Way to make new work for a solo exhibition in my hometown, Burnley, a post-industrial town in North West England. During my time back in the area, I wanted to explore my relationship to the place I knew and what I was met with today. I devised a good exploration of this would be to walk the 4.5 miles along the River Brun, a river that starts and ends in Burnley. Starting in the village of Hurstwood, travelling via green parts of the town at Rowley Lake and Thompson Park, it tumbles over one final weir ending on Active Way as it joins the River Calder near the Town Mouse pub.

On this journey I wrote, made notes and sketches about what I was seeing and how it made me feel: the animal life, plants, surroundings and the ideas and recollections the journey evoked within me. This became a fictional account, the story of Jake who has returned home after many years, not through choice but because his marriage has broken down and he has nowhere else to go. He walks the river to clear his mind and reconnect with where he comes from: ‘Where the River Don joined the Brun he stood where children sometimes throw stones or fish with nets ( . . . ) The red river of the Don had white dots on its surface like spit. Jake looked back up the Brun and from afar saw a heron stood in the water completely still like a coat of arms’. Extracts from this story are included in the You can never really return home book that accompanies the exhibition.

Monument (2020) documents rural walks taken during the ritual of daily exercise permitted in lockdown at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. It is artist moving image and poem; a meditation on the countryside in my native Lancashire, England, its humble beauty and a commemoration of the communal experience at the height of the pandemic and its subsequent social isolation. Working with the archive at Spot On Lancashire, an arts organisation staging theatre and arts events in rural parts of the county, I selected photography from their collection that act as fragments, and alongside the narration of the poem commemorate the shared memories, intimacy and closeness of such communal experiences, marking the impact of the arts in these often remote, ignored and neglected places and advocating for more.

I recorded my journey every day creating a bucolic visual diary documenting the verdant landscape and a countryside bursting with life, changing from spring to summer. In the film these pastoral glimpses are saturated, a paean to colour where we see them anew. Lysergic, abstracted, the imagery exists in a blurred reality of folk stories and memory, all at once a mind’s eye view from the monument on the village green, the stationed American serviceman and travelling charlatan clairvoyant.

My work relates to the key issues on climate and sustainability this way. Artwork that harangues or preaches, is too earnest, judgemental or is overly moral isn’t for me. Neither do I want to threaten, create doom and panic. I want my work to invite people in, to engage and debate, and discuss ideas that elevate the public discourse.

With regards to the materials, processes and techniques you use to produce your work, are there any practical decisions you make with regard to climate change and sustainability?

During the past few years, a number of my visual arts projects have been text-led which has resulted in books being published of my writing. For A Modest Show in 2022, Blancmange was a publication and artist moving image work which tells the story of one last party of overflowing plates, fistfuls of chips and blancmange on a pedestal. A two-way dialogue between the mysterious host of a seemingly endless, fatal banquet and a nameless character who has arrived to eat himself to death, gorging on memories and enormous amounts of French cuisine.

Another publication, Recreation (2023), is a disorientating story of time travelling bus station clocks, backstreet cycle speedways, portals between lock-ups and the local petrol station a spotlit road movie. The main protagonist tours a post-industrial landscape of lovesickness and yearning, a psychogeographic dream hovering the line between inner consciousness and outside life. Both the first editions of these books were two-colour risograph prints at ethical MARC The Printers in Salford, Greater Manchester. This is as “green” a process as printing gets, using soya-based inks printed on recycled paper and card.

I try to be guided by ethical principles when making decisions about my work and projects. I admit it is not easy though. In the reality of the industry we are in, the often tight budgets allowed to artists makes it very difficult. However, where possible we can endeavour to always produce progressive outcomes when considering climate and sustainability. For example, in my installation Something exotic and euro in 2023, there was a sculptural piece – a pile of thousands of single page, A4 copies of my poem Recreation. All printed on recycled paper.

For You can never really return home (2025), I created a reading room at the back of the gallery. I partnered with the only local second-hand bookshop nearby and curated a selection from their titles for sale. It was a literary show but also, the aim was to encourage reading and sharing books in a place (Burnley) with few bookstores, where the library has been depleted by cuts, and do so in a way that reduces waste and is sustainable.

In general, how do you feel galleries, art spaces, artworks and artists might be able to contribute? What if any role do you feel they can play in a progressive conversation?

Having worked with and in galleries and arts institutions, I have seen good examples. Whether that is efforts to build the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals into work habits, or keeping an allotment, composting, recycling, raising awareness of the conversation through platforming practitioners who are climate conscious, invested in methods of low carbon art-making and exhibitions, or activity and programming discussing the fact like climate action events, there are positive intentions in our industry, individuals and organisations leading on climate and sustainability strategy.

Julie’s Bicycle are doing great work, mobilising the art and culture sector, making tools and frame work accessible for galleries and art spaces to act on the climate, nature and justice crisis. In 2021, I attended Framework for Resilience an online talk at FACT, Liverpool, about ecological empathy. Writer and activist Céline Semaan was a speaker, Creative Director of Slow Factory working at the intersections of climate and culture. This platform is a strong ally for environmental and social justice and community action, sharing knowledge and educating, and providing tool kits and solutions using a liberatory framework centred in sustainability literacy and culture. Everything is Political, a project of Slow Factory, is free independent media, a platform and periodical and is a good place for informed, diverse writing about culture, climate and politics. Also, personally, I am invested in the conservation of Venice, Italy. I visit the Biennale and as an artist I did a residency there in 2019 – I am passionate about its protection. I follow the campaigns of We Are Here Venice and Comitato No Grandi Navi – fighting for the extinction of cruise ships in the Venice lagoon, and restoration and protection of the ecosystem there. I feel this struggle is a microcosm of the greater struggle we are facing globally.

A commitment to equality, equitability, inclusion and environmental sustainability I strongly identify with as values to live every day and should lead decision making. For a residency in Chemnitz, Germany, for the Begehungen arts festival (2019), myself and the organisers arranged I travel there from the UK via rail to reduce our carbon footprint. For me, it is about starting from an ethical standpoint and doing what I can. Budgets make it difficult, but if we shine a light on the positive things being done and regularly discuss and reflect on what more can be achieved, we can continue to influence and make real progress.

Are there any tips or advice, anything you have learnt you might want to share with other artists or our audiences?

I tell myself to always seek knowledge and try to share best practice on the subject. Try to be flexible, move with the discourse and always have greater ambitions to do things more ethically. If I am always thinking this way – I am considering others, my community, locally and internationally. I try to keep this at the forefront of my mind when considering how I live, my practice, projects, materials and exhibitions. I am saying this as much to myself – for my own benefit – as I might do to other artists or our audiences. It is not easy but simply, if we all do what we can and try to be more ethical towards climate change and sustainability, it will add up to something much greater.

Links

Images

Banner:

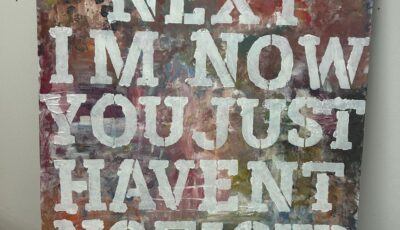

- Elliott Flanagan, You can never really return home, 2025. Photographed by Jack Bolton.

From left to right, top to bottom:

- Elliott Flanagan, Monument, 2020, film still.

- Elliott Flanagan, You can never really return home, 2025. Photographed by Jack Bolton.

- Elliott Flanagan, You can never really return home, 2025. Photographed by Jack Bolton.

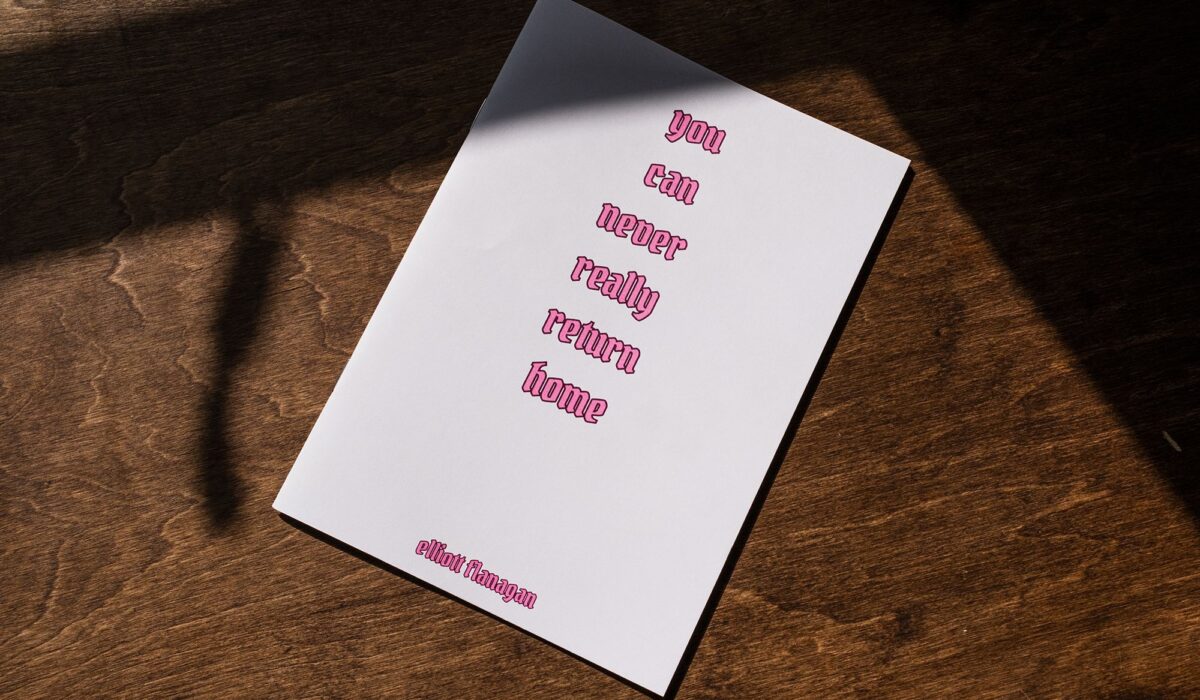

- Elliott Flanagan, You can never really return home, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.