Meet the artists from our graduates support programmes: Adam Rawlinson

Posted on 26 August 2025

For this series, Maariya Daud, who undertook a placement at Castlefield Gallery, interviewed the artists from our graduates support programmes. Today we are meeting Adam Rawlinson.

Adam is one of the 2023-24 University of Salford Castlefield Gallery Scholars. He works primarily in oils to explore our human relationship with the earth and ecology. Through philosophical enquiry, Adam interrogates the act of looking and of phenomenology, providing spaces of contemplation and reflection.

Who have you been mentored by to date; what do you like about them?

My mentor was an artist called Gregory Herbert. We visited Greg at his studio in Liverpool during one of the several trips on the scholarship. We travelled to Northern cities across the time on the programme, visiting studios, galleries and artist-led spaces. These were an invaluable opportunity to speak with artists, directors and curators to gain a better understanding of what they do and build relationships that breached city boarders. On several projects Greg has worked with and around lichen as an interest. I already knew of Greg’s work beforehand, so this opportunity to discuss with him and see his working space was really great. Greg had done work collaboratively with people working in scientific fields, and so I would talk with him about potential things that may happen on a travel scholarship I had a few weeks after. It became clear that our work had several overlaps. While we work within very different mediums, this was someone whose work I admired and ideas I felt explored shared issues and interests. In the role, he was brilliant to work with. The way we worked opened up my thinking in several directions, through an enthusiastic and suggestive attitude, which also remained reflective and dissective. We found ways of thinking around every aspect of my practice. Inspired by our conversations to take a more proactive approach to my practice outside of the studio, I joined the British Lichen society (BLS), where I enrolled on an introductory course into Lichens and Identification. It was good to have lengthy discussions with someone with experience and knowledge on certain topics which helped lift my practice. His generosity of sharing ideas and contributing meaningfully to considerations around my practice proved to have a long lasting influence on how I approach art making.

Who (or what) has been the biggest influence on your art to date – and its style?

I owe a lot to lichen, they helped me see the world differently. I had something of an epiphany a few years ago, whereby I realised I knew nothing about lichen at all, not even the term ‘lichen’. Yet, I saw them almost every day, without much inquiry into what they were and why they were there. Since then I am inquisitive about almost everything, especially within the natural world, and I have researched lichens to great depth since, including a two week self-led research trip in the Scottish Highlands. The role this research plays within my painting is through metaphor. A metaphor for looking. I want to engage the viewer through how I paint to actively look at my work, through crouching, squinting, moving back and forth in the space in front of the work; it is through these actions the viewer gives agency to the painting and it becomes alive! In terms of artists that influence my work, there is an ever-growing list of artists who play an active role in how I approach painting. From their use of painterly techniques to influential ideas expressed through writing about art. Though my influences are always evolving and changing, certain artists are always present in this conversation. The works and practices of Joan Mitchell, Gillian Ayres and Howard Hodgkin are a defiant and constant influence inside and outside of the studio, along with the words and writings of Agnes Martin and Phillip Guston.

What is your most successful work to date? Was there a long process behind it, a thought process perhaps?

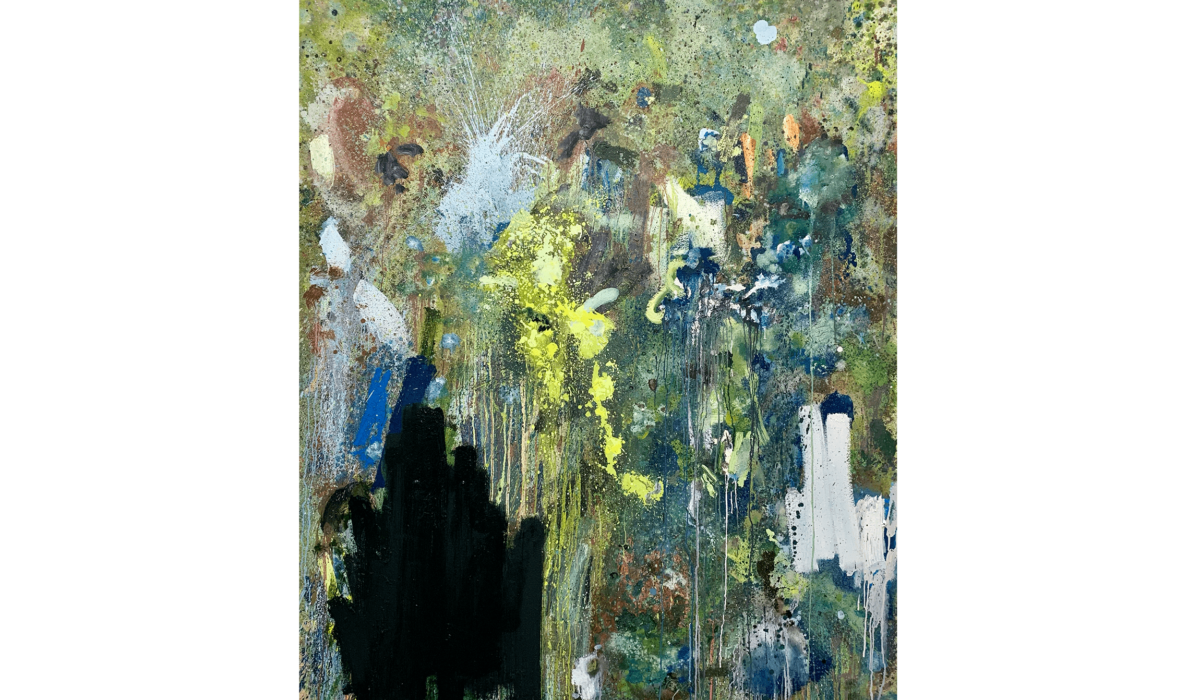

I don’t tend to have preferences over my own works. I am always critical and restlessly unsatisfied with the work I make. Instead, I often find myself favouring smaller drawings and sketches, hanging or keeping them for myself. When an idea is captured through something so simple, it’s a beautiful thing and something to be celebrated and cherished. It’s rare. I try to be as simple as I can when I paint too. Though the process I have developed in the last few years is a long and laborious one, there is always an attempt to be as clear and as simple as possible. There are no short cuts in painting. In a seemingly contradictory sense, it takes a long time (and a lot of paint) to get the work to a point where it is as simple as it can be. The last few paintings I have completed have taken upward of four months each to finish. In this time there is countless layers of paint applied to the surface to achieve an ‘all-over’ effect, which results in each painting having splashes, flicks, pours, stains, marks and thick areas of impasto, so that every area of the canvas contains a multitude of gestures, colours and textures. This method of painting is rooted in the context of how I want the work to be seen, felt and engaged with. If a small area (smaller than your fingernail) of a large canvas (160cm x 200cm) is filled with an array of gestures, movements, different colour relationships, different painterly techniques, evidence of a range of paint application, brushstrokes, stains, drips, pours and both accidental and deliberate mark making, this draws the viewer in for a closer look. A squinting look at the intimately small details which account for the making up of the work as a whole. Much like leaning in to closely examine the intricate forms of a dusty lichen sitting on a rock or the dangling fine lichen from the bark of a tree or the rigid leafy lichens spread over a fallen branch on a forest floor. It is within these moments you feel and understand that these often-unnoticed organisms are significant within the wider picture of the ecology, recognising that we sit amongst the many millions of organisms that make up the world around us. What can be seen in a small area of canvas is reflected in the work as a whole. Visually and theoretically, each small mark on the surface contributes significantly to the whole painting. Therefore, each painting requires a lot of time to reach this stage whereby then the painting can begin to ‘happen’.

Do you think you had a decisive moment where you realised what your art style was?

My pathway and interest in art first came probably around the time I was 20. This meant that the first time I had an art education was at university, where I was starting from scratch. My tutors at the University of Salford were excellent in encouraging experimentation, which proved to be extremely valuable, and fostered in me a ‘learning through making’ attitude that I still carry with me. I was able to try new and different mediums, which was really important to understand what worked and what didn’t work for me. I worked fast and shifted between disciplines quickly, as a result I made lots of work. The studio was a safe place to ‘fail’, learn and try new things. This was really important for me as an artist at this stage. As I whittled down my area of practice and progressed through the years there, my focus became sharper and it was clear that abstract painting was the most suited for what I wanted to do. With continued practice in the studio, combined with reading around and within the subject, I identified with the language and aims of abstraction – it became a perfect vehicle for my ideas and became the starting point for my practice as it is now.

How do you feel about your art now, compared to a year ago? How has the mentorship programme changed the way you view your art?

I feel balanced, between the comfort of confidence that comes from developing further an understanding of one’s practice and ideas, against the constant pursuit of questioning which pick holes, prods and makes wobble what I once thought of as concrete ideology within my thinking and making. In this vein, throughout the programme, I have meandered through the push and pull of these factors. Investigatory questions are brilliant at exposing conceptual ‘weaknesses’ within a practice, thrusting a shining focus upon areas which are at risk of deflating the structure of thinking behind an artwork. Simple questions. Why do this? Why not do that? Have you thought about doing this instead of that? Why are you using that in that way? Can you try this? Would this help? Can you take this away? Each highlights an area of a practice with potentially devastating effect. Devastating in its ability to break down a way of thinking. This is never a bad thing. I invite being challenged, I seek it out. It provides the glasses to see your work through another lens. It provides an opportunity to dissect and rebuild avenues of thought. It draws the ring, within which you can discuss certain elements, making clear what works and what changes could be made. Through the programme this clarity proved invaluable, as my gaze was directed through areas of my practice that hadn’t been considered in such detail before. Finding the answers to the questions asked meant I began to understand my own work to a higher degree. I now view my art with these same glasses on. Looking and listening to my work in a way that is constantly in conversation with itself, both asking questions and finding answers, from which new avenues of exploration within what I do begin to reveal themselves. Everything has become much clearer. Greg equipped me with the tools to sufficiently become critical over my own work, these same questions are present within the fibres of each canvas I make.

Can you run us through a typical session with your mentor? What does it look like, what sort of things do you do together?

With Greg there was lots of talking. Amy Sillman once said, “Talking is painting!” I therefore approached the sessions not too dissimilar to how I approach an empty canvas. Initially it’s difficult to know where to go, at the beginning the possibilities are numerous. It is only the act of either painting or talking at which things seems to appear and a direction takes place. The same way the paint has an element of control over what is done next, so does a conversation. The more you paint, the clearer the direction of where to go next. The same applies with these sessions. I used to say to Greg, “I don’t know, what I don’t know”, meaning that things that could prove helpful to me, that exist in the world, I remain unaware of, with no path to get there. This is where Greg was exceptional. Through our conversation, there were paths beginning to emerge, revealing areas of interest, that Greg understood would be relevant for me to investigate. He then set tasks and further research both for me, so I could gauge for myself whether or not these new avenues were worth pursuing and also for himself, to see if he could find alternative or additional potential areas of interest. We then fed back to each other and repeated the process, so then as time went on, we shared a much more concise and concentrated idea of where to focus our talking, exploring previous points, with newly considered ways of thinking and doing.

Links

Website

adamrawlinson.comImages

Banner:

- Adam Rawlinson, It’s as real as me and you. And just as important too, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.

From left to right, top to bottom:

- Adam Rawlinson, He was an old man who fished along in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty four days now without taking a fish, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

- Adam Rawlinson, The birds will sing, that you are part of everything, 2024. Photographed by Jules Lister.

- Adam Rawlinson, It’s as real as me and you. And just as important too, 2024, detail. Image courtesy of the artist.